During the Spring 2024 term, Professor Emily Steiner (University of Pennsylvania) gave her students a creative option for their final project:

“Adapt a Chaucerian tale for children (creative, under 600 words) OR design a unit on the Canterbury Tales for middle school/junior high students (approximately 5th-8th grades) (critical, under 600 words). You are welcome to compose either assignment in a language other than English, so long as you give an English translation as well.

“In either case, please be very intentional about your decisions, perhaps inspired by the nineteenth- and early twentieth-models we discussed in class. For which children (and proxy readers) are you writing? For those of you designing a teaching unit, do consider demographic factors, school system, institution, etc. You might consider developing a unit for your own middle school/junior high alma mater!”

Zuza Jevremovic, a student in Steiner’s class, chose the creative option. After studying some old renditions of children’s Chaucer by Charles Cowden Clarke, Mary Eliza Haweis, and Katharine Lee Bates, Jevremovic selected appropriate text and added illustrations.

Below is Jevremovic’s introduction to her project and then the project itself.

************************************************************

by Zuza Jevremovic

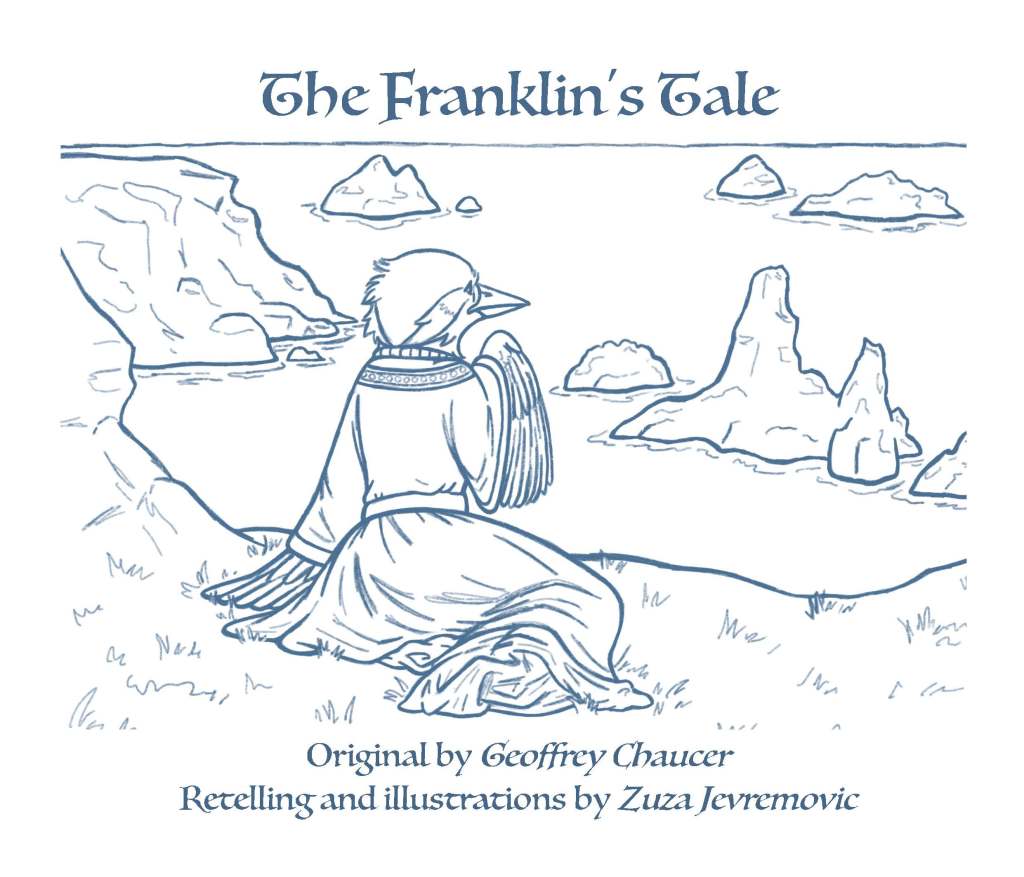

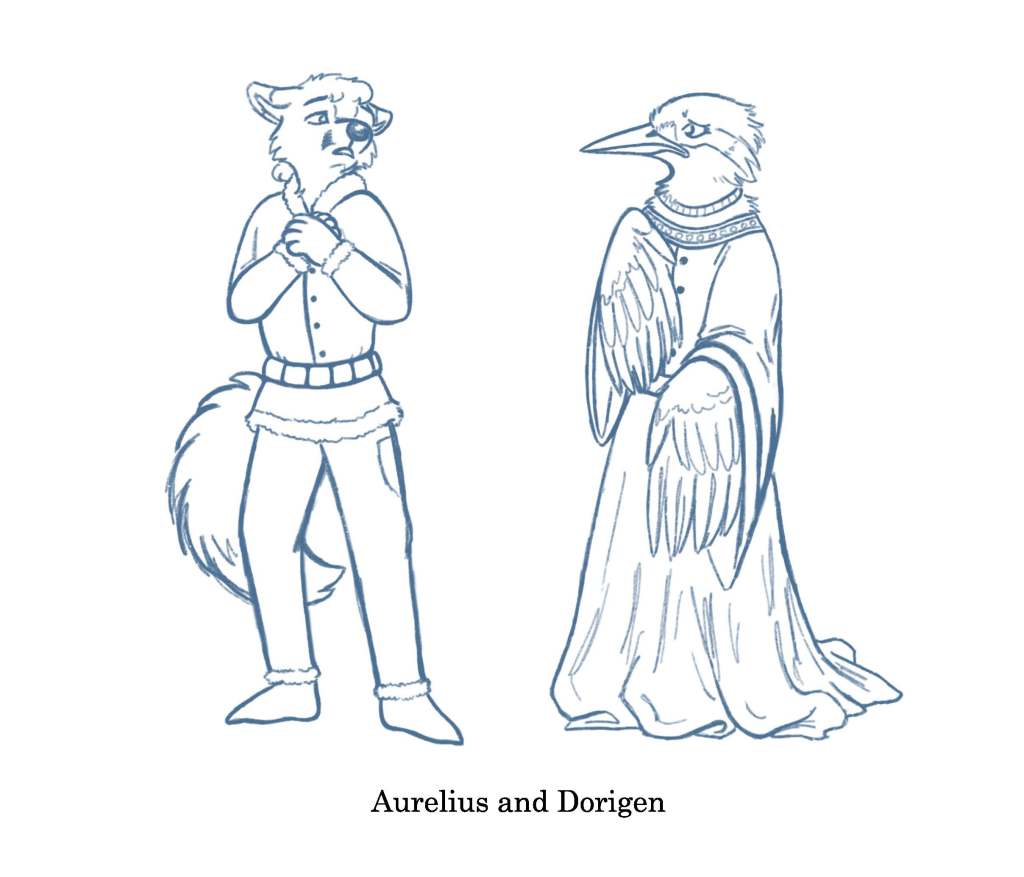

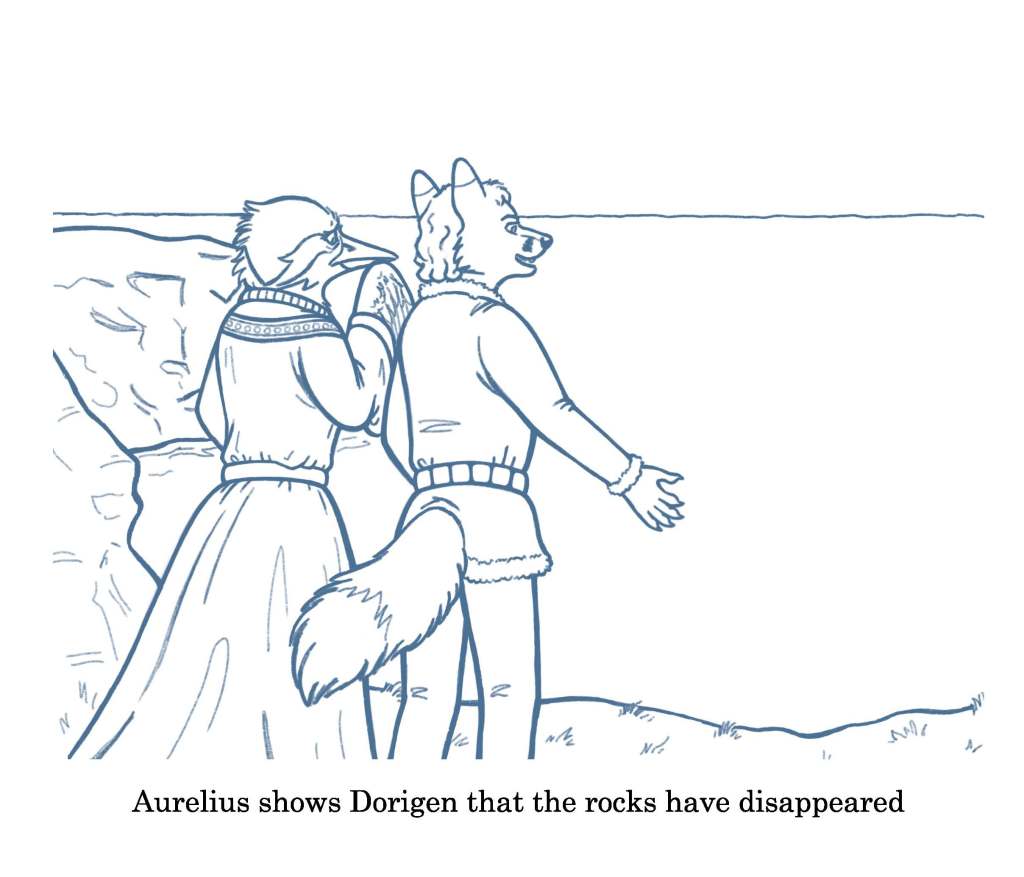

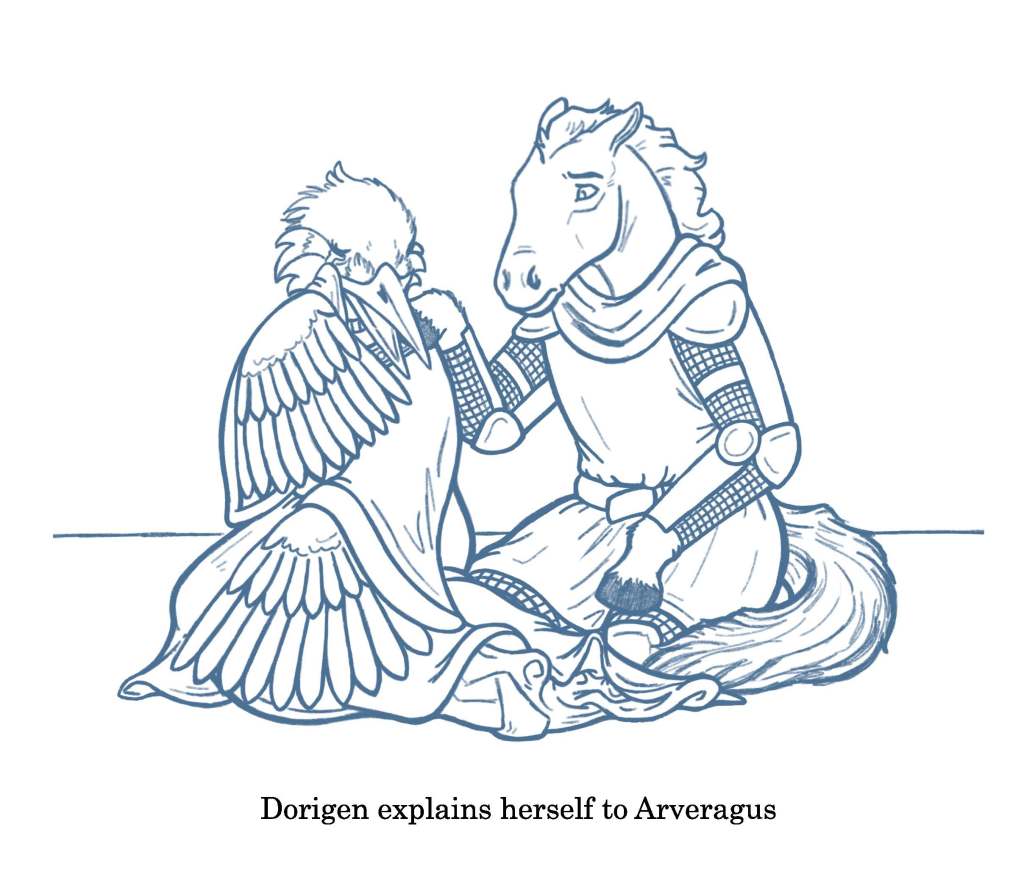

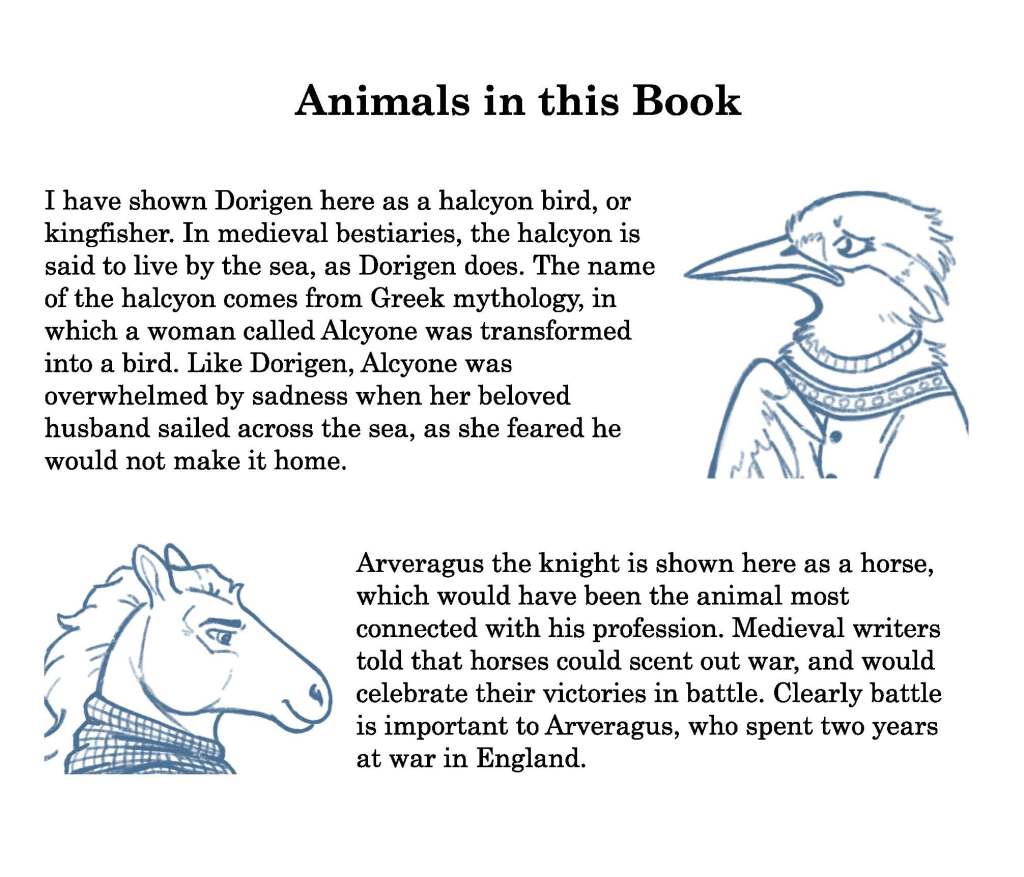

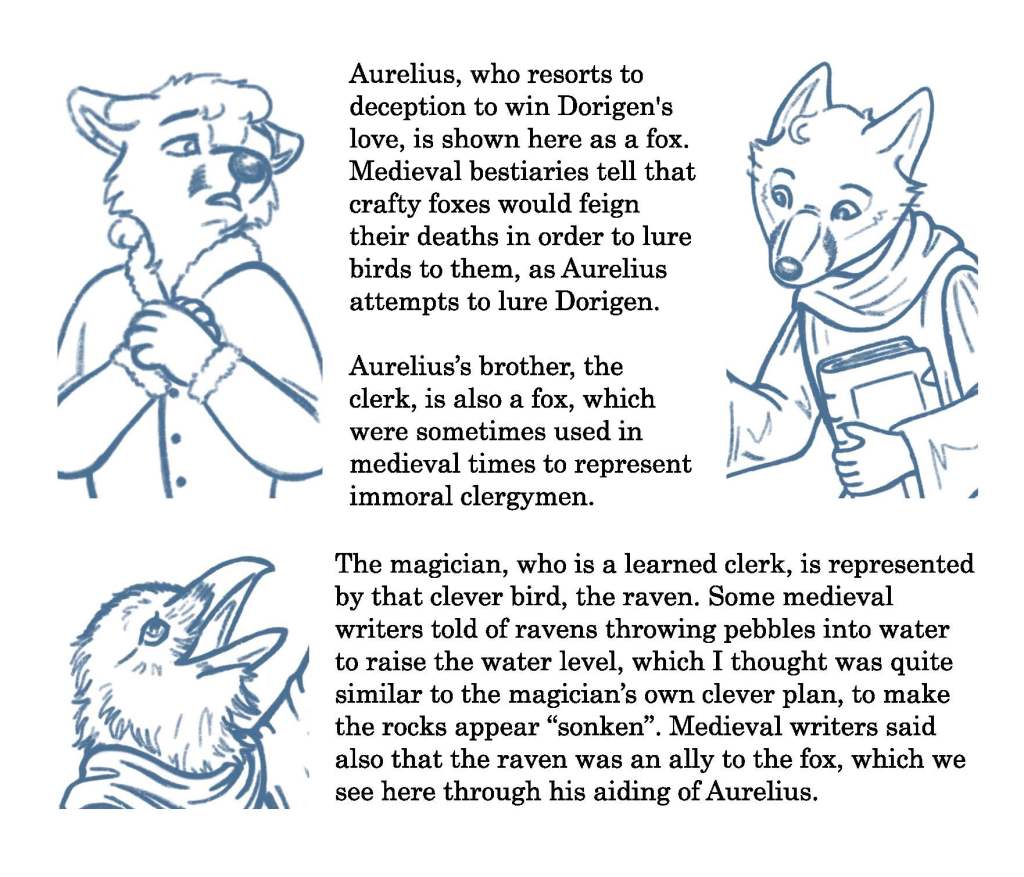

As one whose childhood dream was to be an author-illustrator, I deem no children’s book complete without illustrations, and in fact The Franklin’s Tale lends itself well to this. It is a story about seeing, even when sight does not match up with reality. As the clerk’s magical illusions transform his house into a fantastical forest, a picture book may do similar for a child’s imagination. I hope my illustrations—and the use of animals to differentiate and symbolize characters—might engage readers more in the story’s magic than would the text alone. Pictures can also help to illuminate characters’ emotions and relationships, shown here through expressions and body language.

I created these illustrations with Procreate, an iPad drawing application which I have been using for years and am well accustomed to. While I also enjoy creating paper-based artwork with colored pencils, I felt digital work would be less time-consuming here, and would enable me to edit my sketches much more extensively. However, the brush I chose is still intended to evoke something of a traditional pencil feel.

Beyond its visual inclinations, I chose to adapt The Franklin’s Tale on account of its relatively child-friendly story, compared to the other tales we studied. The main complication in its morality is the point of Arveragus giving up his wife to a suitor whom she did not want to be with; even the original tale acknowledges potential audience concern about the knight’s decision, so I have preserved that narratorial comment. Otherwise, Arveragus and Dorigen’s marriage seems far healthier than most other Chaucerian couples; their equal standing and patience with each other translate well into the modern day as moral virtues. In my rendition, the nature of their relationship is more ambiguous, not confirming marital status so as to reduce the complication of the relationships and conflicting promises. I have also tried to clarify the characters’ motivations, contextualizing Arveragus’s actions in his knightly profession, explaining why the rash promises were made, and making clear Aurelius’s moral faults.

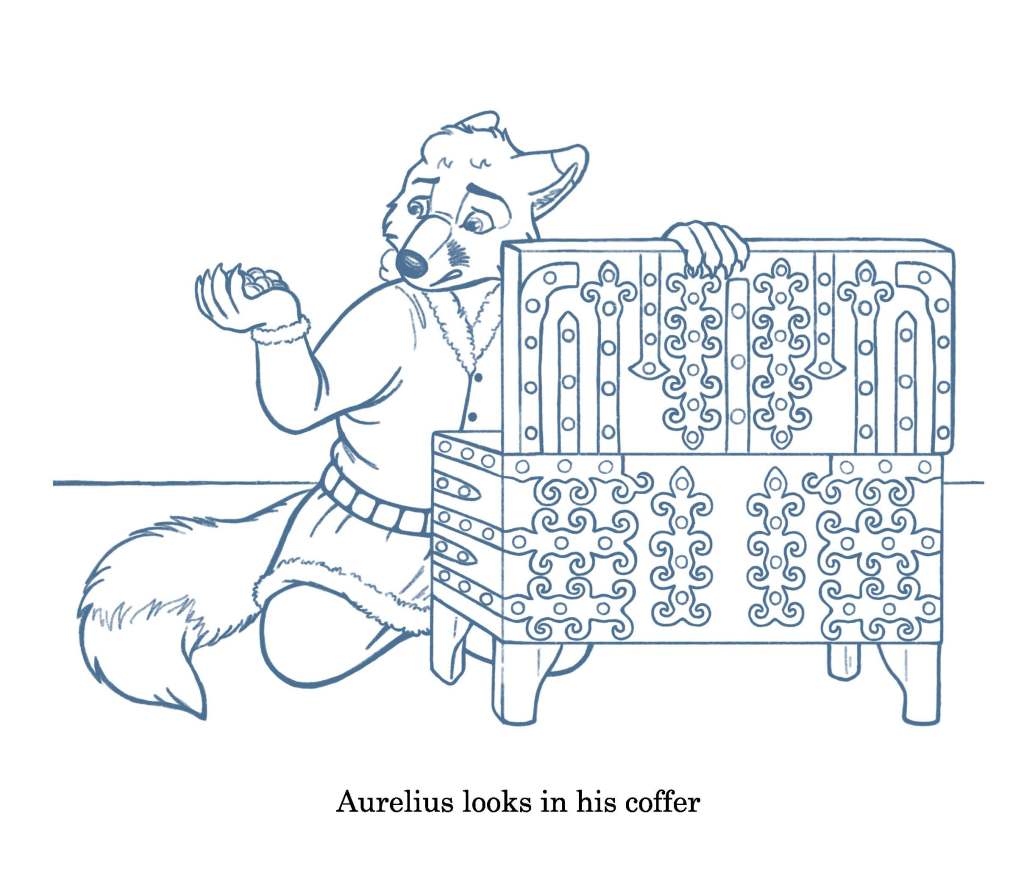

It is customary for children’s adaptations to feature a moral, so this replaced the Franklin’s original concluding question (the suggestion of Arveragus’s “generosity” did not seem appropriate to include). The moral proposed in Mary Eliza Haweis’s Chaucer for Children—which we looked at in class, and which inspired some outfits in my illustrations—was to “beware of the folly that Dorigene committed, in making rash promises”. This makes sense, but it occurred to me that this applied equally to Aurelius, who rashly promised the magician money he could not pay. Thus, I tried to place extra focus on this plot point in my own story, even devoting an illustration to Aurelius’s coffer. Ultimately, neither Dorigen nor Aurelius was punished for their mistake, which I attributed here to their willingness to come clean. This provides for a gentler moral, as naturally children (and all people) will make mistakes; at least there is hope that honesty may alleviate the consequences.

*************************************************************

Leave a comment