by Jacquelyn Hendricks

At the end of 2024, I learned about Jacquelyn Hendricks’s recent article that brings together Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale, J.K. Rowling, and social media. Published in the Summer 2024 issue of Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, Hendricks’s article argues that Rowling’s appropriation of not only Chaucer’s account of the three rioters but also his framing device invites us “to engage more critically with Rowling and her work, to be wary of the seemingly positive message it contains, and to let the trans and nonbinary communities lead us in our response.” Because I like to share how other fields help us re-vision the ways we teach Chaucer and other medieval literature, I invited Hendricks to share ways we could bring these insights to our classrooms and our students. I especially appreciate the parallels she draws between fourteenth-century The Canterbury Tales and twenty-first-century social media. Even more, I appreciate her sensitivity to the concerns students bring to our classrooms and their reading practices. –Candace Barrington

When we teach “The Pardoner’s Tale,” so many of our lesson plans hinge upon the question raised by the Pardoner when he says “for though myself be a ful vicious man, / A moral tale yet I yow telle kan” (459-60). In my recent article, “A ‘ful vicious’ author: Examining J.K. Rowling’s Transphobia through Her Framing of Chaucer’s ‘Pardoner’s Tale’” (Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 2024), I use this question to reflect on J.K. Rowling’s transphobic social media posts and their effect on her readers. I compare Chaucer’s and Rowling’s framing devices as a means of distancing the author from the text, and I do a lot of social media analysis of Rowling’s Twitter/X. I ultimately suggest following the lead of the trans and non-binary community in how we engage with her material. Because it intersects Chaucer, Harry Potter,and social media, it’s an article that you might find useful in your classrooms, and in this post, I’ll offer some suggestions for how your students can apply similar methods in classroom activities.

Social media platforms can be a great way to engage with the question of how artists’ behaviors affect our reception of their art, allowing us to teach our students greater social media literacy. The Canterbury Tales is, in so many ways, a form of social media – pilgrims share stories for “likes” from the group to win the dinner offered by the Host. They voice comments in the prologues, epilogues, and even occasionally interjecting in the tales themselves. They troll each other. In particular, the Pardoner himself is “cancelled” by the Host who shuts down the Pardoner’s attempts to get him to “kisse the relikes” (944) by saying “I wol no lenger pleye / With thee, ne with noon oother angry man” (958-9). Even the Knight’s attempt to get them to kiss and make up mirrors our contemporary resistance to the idea of cancelling anyone permanently.

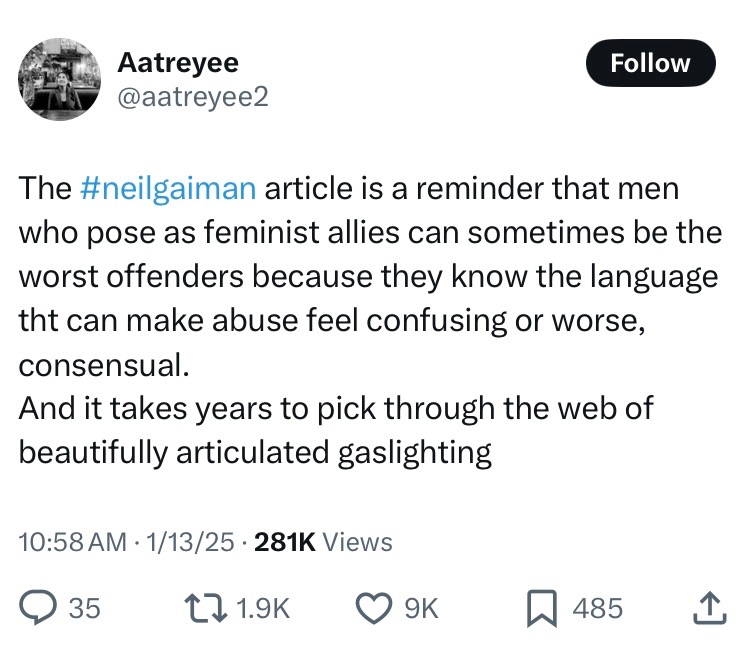

Many of our students are wrestling with the problematic behavior of influential artists that is often played out on social media, especially because of the unfettered access that celebrity social media accounts provide coupled with a 24-hour entertainment news cycle that puts them under a constant spotlight. This has led to the rise of cancel culture, where celebrities and artists can be boycotted by their fanbase because of their words and actions. Whether these cancellations are warranted or not, the phenomenon of cancel culture should make it clear: to our students, the author is not dead. They desire to consume art, culture, and other forms of entertainment by creators who reflect their values and represent diverse identities. Recently, many artists whose values seemed to align with the messages in their art have shown themselves to be wolves in sheep’s clothing. In addition to J.K. Rowling, media consumers have notably grappled with the news about Neil Gaiman’s alleged sexual abuse and Kanye West’s antisemitism and perceived exploitation of his wife, and it seems that nearly every day a celebrity crosses a moral boundary in the eyes of the public. With this in mind, here’s how your students can reflect on the question of “vicious” content creators by using social media as you teach “The Pardoner’s Prologue and Tale.”

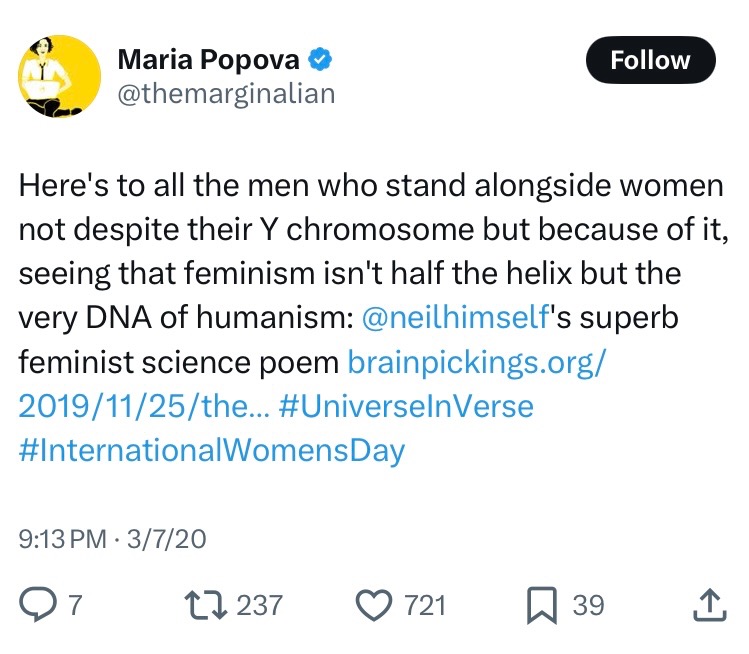

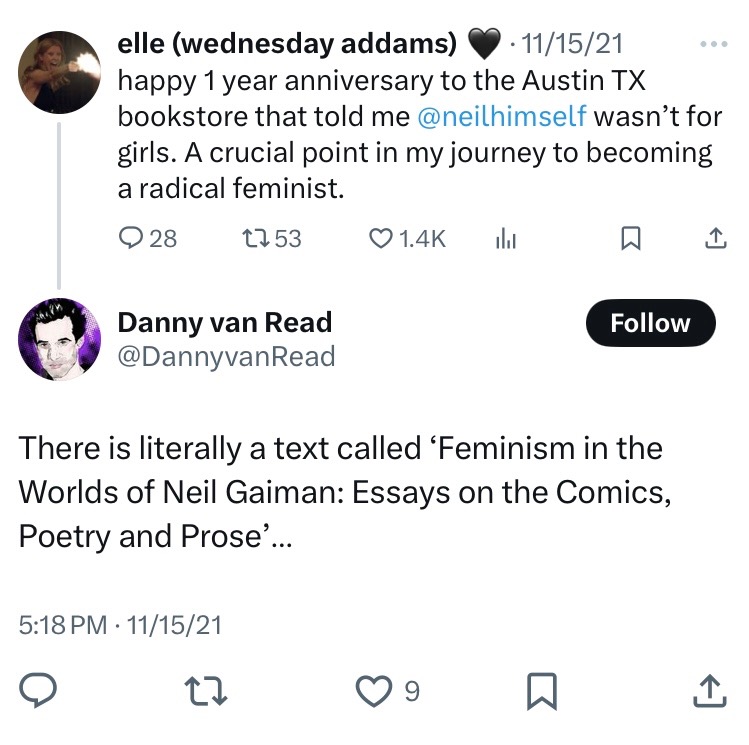

Use social media posts to show how celebrities create a brand of themselves that aligns with certain values and communities. For the Pardoner, the prologue functions as a “social media platform” for him to state his values, which ultimately undermine the brand of religious leader he attempts to sell in his tale. In many ways, this draws a direct parallel to J.K. Rowling’s transphobic posts on Twitter/X. As I discuss in my article, her books have been shown in studies to teach empathy to her readers, and she built a brand of herself in the past as supportive of the LGBTQ+ community. Her posts, however, have actively contradicted her books’ messages on empathy and her brand as an ally.

This exercise can give a modern touchstone to the discussion of whether or not value can be taken from an artist’s work once they do something worthy of cancellation:

Have students build a celebrity/artist brand profile:

- Invite students to choose any celebrity (controversial or not) and, by reviewing their social media, have them define how that celebrity is branding themselves.

- Ask them to review comments and shares of those posts to see what fans value in the celebrity’s brand.

- Have them assess how that celebrity’s art reflects their brand.

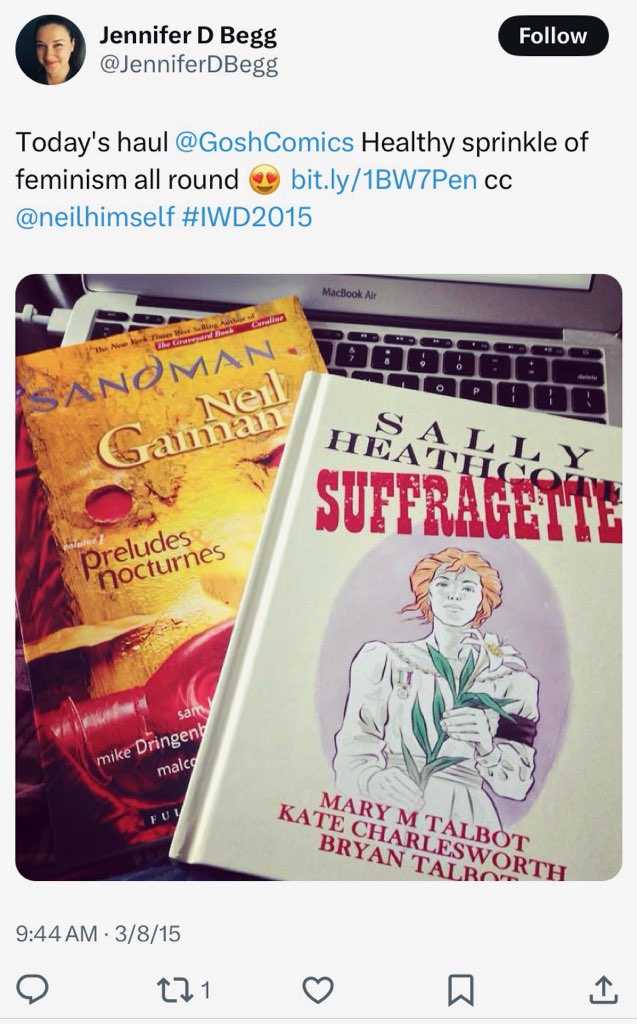

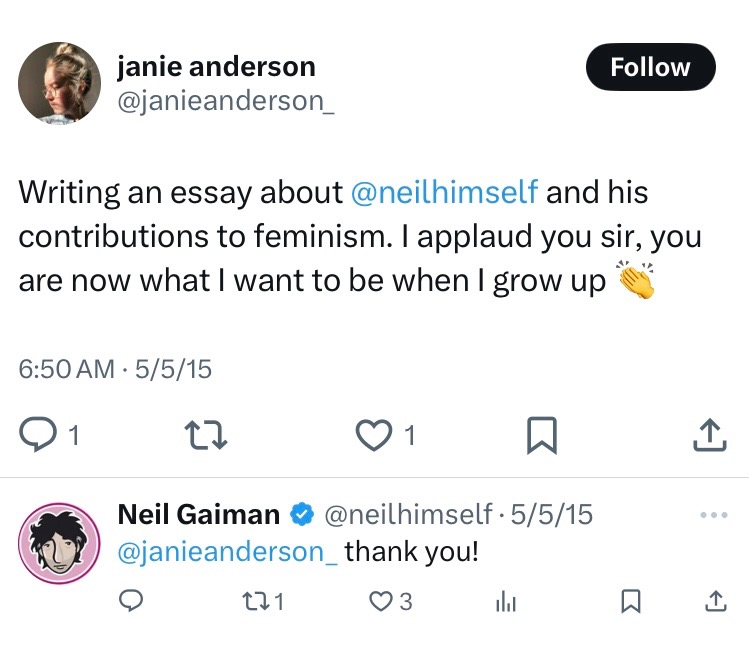

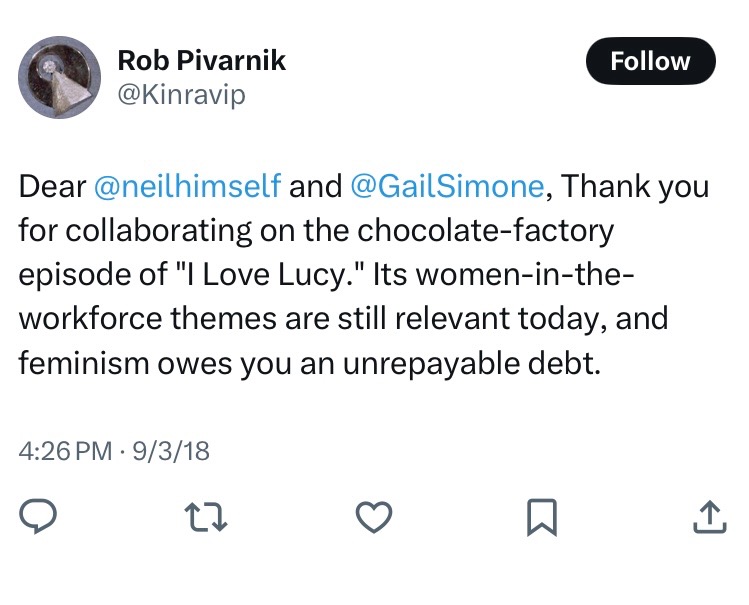

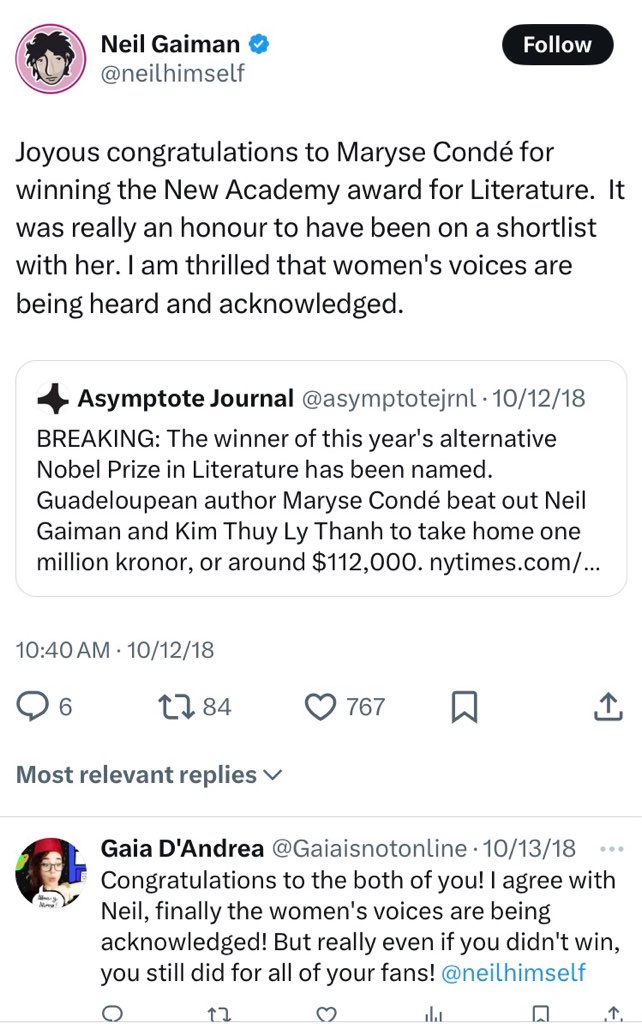

These examples come from Neil Gaiman’s social media feminism branding, some before, some after, the allegations.

Then, ask students to think about whether or not it would affect the meaning and reception of their art if the celebrity’s actions began to violate their established brand, or if they were to change their brand to something more “vicious.” Some questions you might ask include:

- What kinds of celebrity brands are most affected by cancellation? Which ones are less affected?

- What kind of things might someone be cancelled for that would affect the reception of their art? Which things might have less of an effect? (For example, stances on political issues vs. crimes that harm others.)

- How does their degree of creative control over their artwork affect the meaning and reception of their art if they’re cancelled (a director or author vs. an actor or model)?

At this point, it can be useful to invite students to reflect on “vicious” celebrities and artists. Students often want to speak on how they’re wrestling with the bad behavior of creators of beloved books, films, and music. This conversation can also remind them to think about how directly harmed communities are responding to problematic creators – many students may dismiss the “viciousness” of artists because they are not directly affected, but considering other perspectives can allow them to see that creators’ harms result in more than simple disappointment from their fans. Since this is a rather personal reflection, it may work best as an in-class writing assignment followed by a conversation where you invite a few who are comfortable to share.

- Who are celebrities / artists whose work meant something to you or your community but then they did or said something harmful?

- Which communities have their misbehavior affected? How have those communities responded?

- Have you decided whether or not to “cancel” them yourself?

- Whose voices are you considering as you decide how to respond?

- What does it mean to you to “cancel” a celebrity / artist you were a fan of? What specific actions would take / have you taken?

My student, Elijah Goss, reflected on the importance of Kanye West’s music to the Black community (which the student is part of) and how to grapple with that in light of his recent antisemitism: “Hatred directed towards others solely based on their identity is inexcusable, and ignoring those actions will only enable harmful behavior. But we might recognize the dichotomy between harmful actions and positive influence. Kanye’s antisemitic rhetoric is serious, especially given his platform’s reach. At the same time, his music and actions outside of art have made a tremendous impact on the African-American community. Neither of these things excuse the other, but we must consider the complexity here: two things can be true simultaneously.”

This celebrity brand analysis and discussion of the effects of cancellation can allow students to think more deeply about how the Pardoner brands himself to preach his sermons and convince people to give him money, and why violating the values he purports in his brand can solicit such a strong (and violent) reaction. (It’s an activity you could potentially apply to other pilgrims as well – thinking about how the brands they build of themselves are supported / not supported by the “General Prologue” and/or their tales.)

These activities can provide students a clearer understanding of the gravity of the Pardoner’s question. In my classes, when students are asked whether or not a “vicious” person like the Pardoner can tell a moral tale, the responses are always an automatic yes at first. But putting a familiar face on the concept of a “vicious” storyteller or artist, or delving more into the responses of communities they’ve harmed, can help students understand that it isn’t as simple a question as it seems. Moreover, there’s an urgent need in today’s political, cultural, and social climate to develop greater social media literacy and cultivate methods for growing empathy for marginalized populations.

Leave a comment