By. Sandy Feinstein, Nicolas Fay, and Bryan Shawn Wang

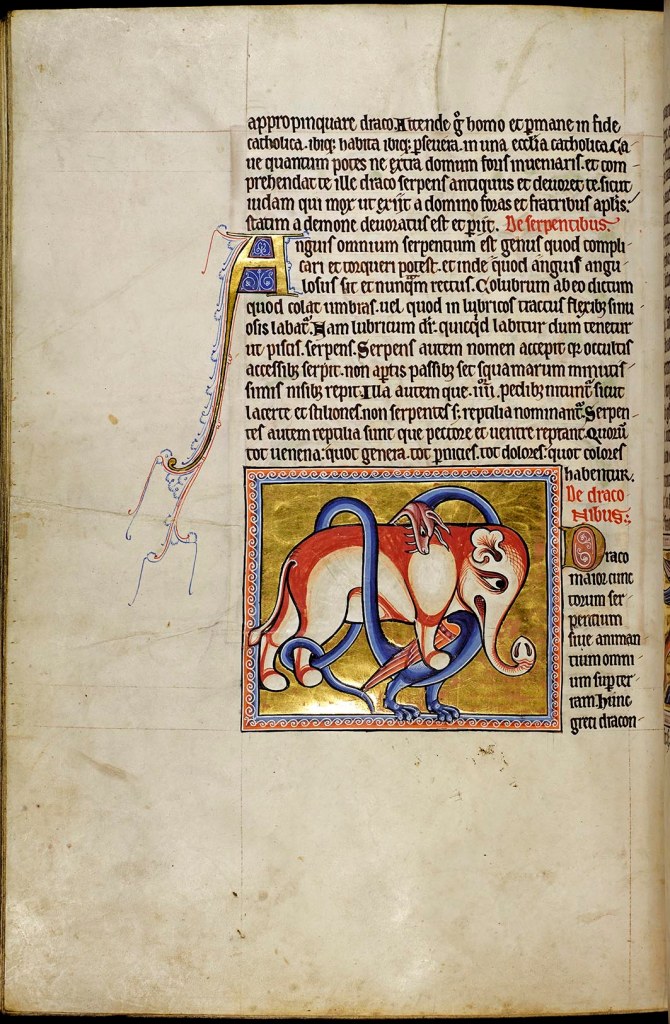

University of Aberdeen, https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/jpeg/f65v.jpg

Well, that’s what we told the students: that they’d be learning how to resurrect a dinosaur. But that wasn’t my part; that was the task for the molecular biologist. My role appeared to be innocent, focusing, as it does, on old books. There are no dinosaurs in the bestiaries, not at any rate what a modern reader might recognize or call T-rex or Brontosaurus or Triceratops. There are Bonnacons and Monoceros and Dragons. Monoceros are more familiarly known as unicorns. Bonnacons look like bulls, but they have a secret weapon. And Dragons, more familiar all the time, or so it appears, if you watch tv or go to the movies.

But the dragons and the unicorns are all captives in a kind of Jurassic Park—CGI creations with back stories involving wedding gifts of giant eggs or secret wars with other species, if not restorations and resurrections in the scientific sense. “It’s all his fancy, that” as the Griffin says to Alice about the Mock Turtle.

I know.

Once upon a time, is how you might expect an old, old story to begin, and so it does: the time was very long ago, when Aristotle wrote his natural history. He wrote about all the known creatures of the world, not just what he could see for himself in Greece, but what Alexander the Great collected for him. There were a lot of animals. He tried to understand everything he could about them and when he had enough information, he tried to order the creatures: those that crawl on the ground, those that live in the sea, and those that fly through the air.

The restoration biologists stick to dead things. Things with extractable DNA. The passenger pigeon massacred by man brought back to life by same. The ivory-billed woodpecker too big for its diminished Tennessee swamps. Anyway, you get the idea. Very scientific. Science with a touch of would-be aspirational intention, if not conscience.

I figured if scientists could decide who lives, dies, and is returned to new pastures, then why not me. If you read, or go to movies, you know there are humanists that use their powers: symbologists uncovering the grail, enigmatologists reading runes that tell the future. I wanted more. I wanted, well, I wanted a few of the oldest creatures, those wrapped in the skins of goat, or sheep, or cow. Those that glowed. Illuminations come alive.

Again, Mr. Science could explain the glowing part. Luminescence. Nothing mythical in those genes. Maybe not, or maybe.

But to make a woolly mouse, never mind a dragon or a unicorn, requires lots of input, expertise beyond the basic idea. Like it or not, there’s no excluding the scientists or engineers. Then to make it all seem legit, having a philosopher provides a moral gloss. Without a chronicler, writer and reader, the process might seem arbitrary, haphazard. That being the case, the first task at hand would, I knew, have to be finding the right team, never mind that literary types like me don’t usually work that way. After some deep thought, and research, though, I think I’ve found the perfect team to pull off my plan: a real scientist and an artist. They create, but also provide the checks and balances to me, the dreamer.

Not even the Gods, including Morpheus, had that. Zeus didn’t talk to the family before changing himself into a swan and a bull, nor did anyone think twice when turning Narcissus into a flower or Daphne into a tree. As for the putative monsters, don’t get me started.

Raising dragons from the page could be a challenge even to this dreamer, not so much to make it happen, as to meet the resistance of the hordes now opposed to reading, especially to reading anything older than their birthdays, never mind working to raise from the page a creature so identified with the devil in the western world. I keep mentioning nice Chinese dragons, but all I get is a side-eye look from the team.

Right. The team. I need to let them introduce themselves and what they are working on. Or why.

There’s Nic. He’s the whole team rolled into one. He covers all the bases. It’s certainly less costly this way. Anyway, he’ll tell you all about who he is or what he’s been doing.

They call me a scientist, but I’m really a designer. Or a curator. Take your pick. I prefer “artist,” but that’s pride. It sounds a little better. More abstract, less intentional. But there isn’t any chance in what I do. Some call me a creator (talk about pride), but I can’t lay claim to that title. Things get complicated fast. “To create, fashion, form,” and “to fit together,” yes. “To bring into being,” not necessarily.

You can see why I like “artist,” although that’s not without problems either. We can start with “workmanship” or “systems of rules for performing certain actions,” but from there, things can go awry. Sooner or later, we end up with “skill in cunning and trickery.” Maybe I’m overthinking things. Yeats talks about art as a process of modification, truths passed down from age to age, altered along the way. That feels right. After all, I’m just using what’s already there and changing things ever so slightly. And what is truth if not nature? But definitions are complicated, so let’s talk about practice–I guess I never really explained what I do. Then you can decide for yourself.

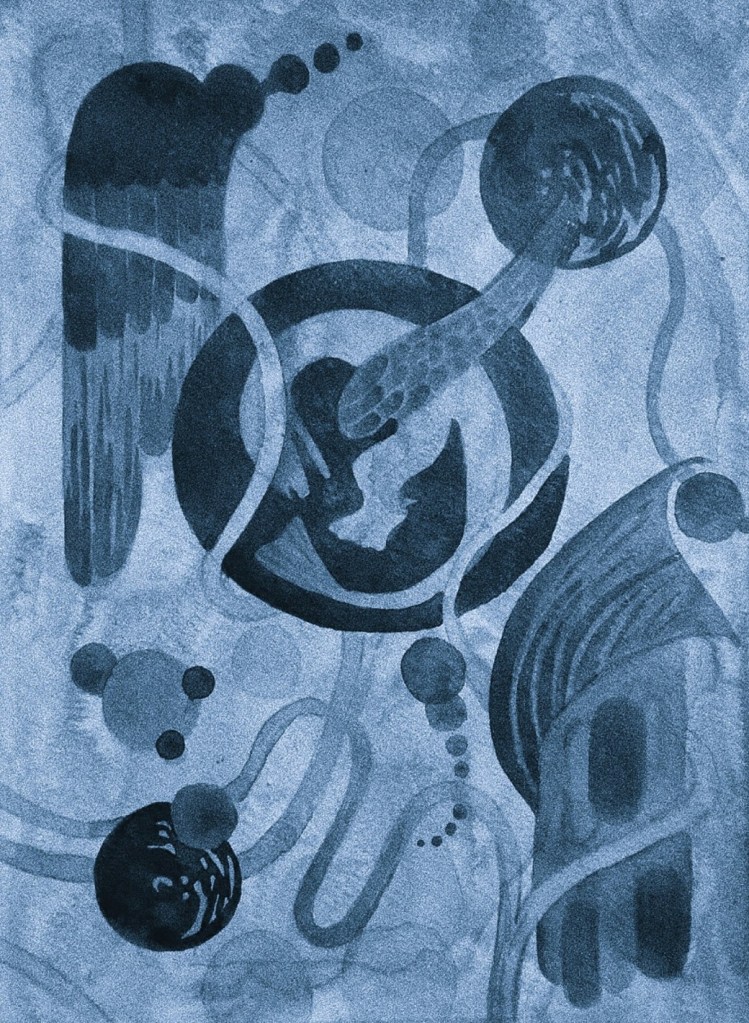

I work with knots, coils, chains, and axes. Spooling, and unspooling. I decide what to alter, adjust. Improve? Lately, I’ve been working with fish. And birds…or birds. Comparing anatomical similarities and differences. Discovering relationships, providing structure and order into which species should be compared, combined. Fins and feathers blur, blend, bleed into each other. Something new.

I’ve been thinking about preservation. Genetic dead ends and survivability. Biological annihilation and adaptation. Nature as truth. We see the physical world as real, as true because it is built on the basis of our senses, of our actions. As we observe, experiment, and bring the fruits of our observations and experiments together, we discover likenesses and differences between events, objects, birds, and beasts. In this way, we establish laws through which we can interpret truth and all subsequent action. But the world to an oyster is just movement, and the world for a jellyfish is just electricity.

What’d I tell you? Is he good or what? Perfect for scraping the ink off of parchment, not just copying it, though obviously he could do that, too. And he’s got a conscience. I mean, it’s not build or bust. He cares.

I admit I’ve gotten into the habit of telling everyone what to do. That’s what’s expected of a teacher, especially one committed to realizing dreams. But this time I’ve let the team go their own way, come up with their own dream, or nightmare, barely prompted.

Still, it’s hard not to push the plan beyond electricity to power more than a jellyfish or its salty wet habitat. And none of the creatures I’m particularly interested in have been so lucky as an oyster—frozen on animal skins as they are, where they are surrounded by words telling you just what you should think about them. Still, they look as if they could move.

So, I asked, “Could you get that monoceros to lift its right leg or poke its horn through to the other side of the verso? Or, since that’s no bird, maybe you’d like to start with the dragon, disappointing as it appears in medieval Aberdeen: just a long snake.” But we know dragons are related to birds, kind of like dinosaurs who it has always seemed to me they resemble, a kind of combo T-rex and pterodactyl.

Figure 1. Natural elements are transformed into artistic material: neck and tail in elegant arcs, wings skewed, mouth agape. Appendages bond, the remainders become one–a genetic circuit completed.

I thought, wow. That’s amazing. All those parts full of vivid lines and so many blues.

But then Mr. Science, the real one, showed me his e-mail, snail mail, web-rants, and I don’t know what. It made me kind of nervous as I listened while he sifted through it all, not exactly complaining, but sounding tired, maybe a little sad. I cut and pasted his last below. It sounded like the end. Of his willingness to be used. Still he seems almost okay with invention, on the page, whatever won’t mess up the gene pools or muck up evolution with speeding up the process.

It’s not my willingness that’s slipping away from me, but my confidence, or maybe my nerve. In any event, the requests pile up: passenger pigeons, quaggas, woolly mammoths. Dinosaurs. (Real dinosaurs.) And crazier still: dragons and unicorns and other fantastical beasts, as if it’s all the same to them. Like switching out the logos for print-on-demand T-shirts.

Well, why not? What we do must seem like fantasy, or magic. We may as well take up wands, don pointy hats, and spangle our lab coats with moons and stars.

We try to deliver. We watch, wonder, test and tinker. We fail, often. We try again.

Early on, we grafted the wings of a vampire bat onto an iguana. Rubbed a paste made from the ground-up horns of an ibex onto the forehead of a thoroughbred horse. Slit a goat’s backside with a scalpel and inserted the severed, still writhing tail of a serpent.

Ludicrously crude attempts.

We devised breeding regimens, seeking to magnify and stabilize even the slightest morphological alteration: the thickening of a bone beneath a fish’s pectoral fins, a distortion of its scales. We discontinued the trials once we understood how slowly Darwin’s clock ticked.

We examined natural variants and sought to reproduce them. We eventually realized they could instruct us. We zapped animals of all kinds with radiation of variable frequencies, fed them chemical after chemical, identified and named the resulting mutants. They led us to genes, which we mapped and decoded. We determined the molecular structure of the double helix, and we learned to break it and paste it back together, to PCR and to CRISPR it. We learned to read the book of life at ever-increasing speeds and to rewrite its words, then sentences, then whole chapters.

We made glowing bacteria, glowing plants, glowing flies and fish and pigs. Proof of the concept, we said. We made useful things from our chimeras—medicines, foods, tools and methods for making better chimeras. Pets. We saw the harm we had done, and we sought to rectify it, restore the world that had been lost. We re-created passenger pigeons and dodos, woolly mice and woolly mammoths. The wall between the living and the dead, between what was real and what was possible, began to crack, and then crumble.

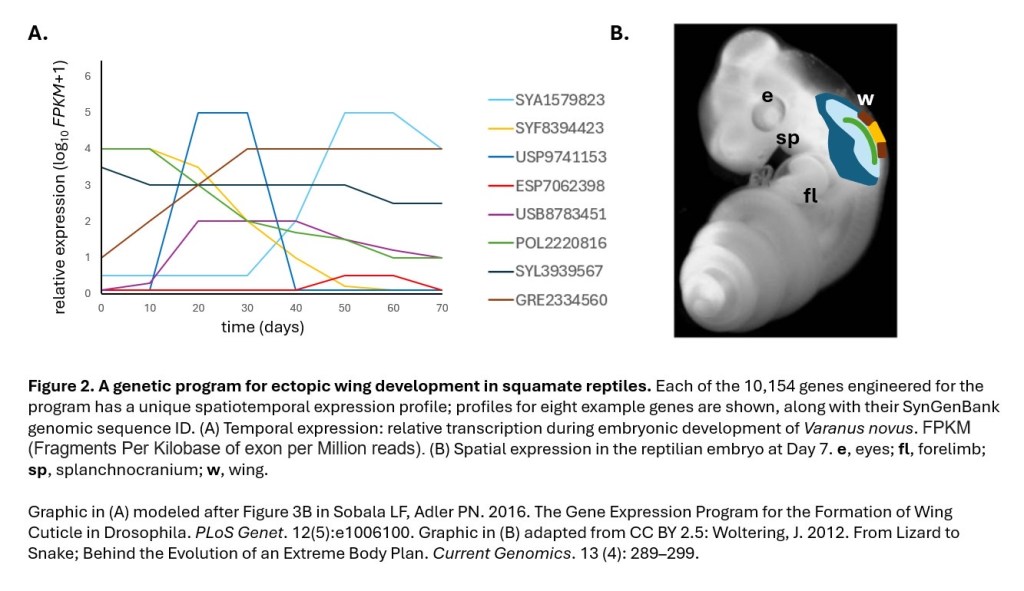

Except where it didn’t. (Or hasn’t.) Because it’s not wizardry but science, constrained by rules established by something greater, rules we may never fully apprehend. We deciphered the gene expression program for wing development in insects, birds, flying mammals with relative ease, but to develop and install the analogous algorithm in a lizard demanded unbelievable resources, human and otherwise. The subroutines for fire breathing, barbed tails, gargantuan size will require the patronage of the gods. The devil is, as always, in the details. The devil is in what we know, and what we don’t know. What we have done, and what we have failed to do. We are aware, partly, occasionally, of our imperfections.

Uh, yikes. Those pictures are scary, really scary. I understand illuminations, well I should say, I suppose, that I love them: their color, the smiling pachyderm, the serpentine dragon, and how one just might save a soul. But those color coded lines? That creepy sand worm like something out of Dune? Not what I had in mind.

It had been my dream, Bryan’s science, and Nic’s art that brought us together to save what we could as we are able—whether creatures on the page or those in the wild. But working with a young artist and a scientist at his peak, while exciting, even fun—reveals so much of what I didn’t understand when I began this project. Hell’s mouth opens, and within may be a different kind of dragon.

Leave a comment